Abelian group

| Concepts in group theory | ||||

| category of groups | ||||

| subgroups, normal subgroups | ||||

| group homomorphisms, kernel, image, quotient | ||||

| direct product, direct sum | ||||

| semidirect product, wreath product | ||||

| Types of groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| simple, finite, infinite | ||||

| discrete, continuous | ||||

| multiplicative, additive | ||||

| cyclic, abelian, dihedral | ||||

| nilpotent, solvable | ||||

| list of group theory topics | ||||

| glossary of group theory | ||||

In abstract algebra, an abelian group, also called a commutative group, is a group in which the result of applying the group operation to two group elements does not depend on their order (the axiom of commutativity). Abelian groups generalize the arithmetic of addition of integers. They are named after Niels Henrik Abel.[1]

The concept of an abelian group is one of the first concepts encountered in undergraduate abstract algebra, with many other basic objects, such as a module and a vector space, being its refinements. The theory of abelian groups is generally simpler than that of their non-abelian counterparts, and finite abelian groups are very well understood. On the other hand, the theory of infinite abelian groups is an area of current research.

Contents |

Definition

An abelian group is a set, A, together with an operation "•" that combines any two elements a and b to form another element denoted a • b. The symbol "•" is a general placeholder for a concretely given operation. To qualify as an abelian group, the set and operation, (A, •), must satisfy five requirements known as the abelian group axioms:

- Closure

- For all a, b in A, the result of the operation a • b is also in A.

- Associativity

- For all a, b and c in A, the equation (a • b) • c = a • (b • c) holds.

- Identity element

- There exists an element e in A, such that for all elements a in A, the equation e • a = a • e = a holds.

- Inverse element

- For each a in A, there exists an element b in A such that a • b = b • a = e, where e is the identity element.

- Commutativity

- For all a, b in A, a • b = b • a.

More compactly, an abelian group is a commutative group. A group in which the group operation is not commutative is called a "non-abelian group" or "non-commutative group".

Facts

Notation

There are two main notational conventions for abelian groups — additive and multiplicative.

| Convention | Operation | Identity | Powers | Inverse |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addition | x + y | 0 | nx | −x |

| Multiplication | x * y or xy | e or 1 | xn | x−1 |

Generally, the multiplicative notation is the usual notation for groups, while the additive notation is the usual notation for modules. The additive notation may also be used to emphasize that a particular group is abelian, whenever both abelian and non-abelian groups are considered.

Multiplication table

To verify that a finite group is abelian, a table (matrix) - known as a Cayley table - can be constructed in a similar fashion to a multiplication table. If the group is G = {g1 = e, g2, ..., gn} under the operation ⋅, the (i, j)'th entry of this table contains the product gi ⋅ gj. The group is abelian if and only if this table is symmetric about the main diagonal.

This is true since if the group is abelian, then gi ⋅ gj = gj ⋅ gi. This implies that the (i, j)'th entry of the table equals the (j, i)'th entry, thus the table is symmetric about the main diagonal.

Examples

- For the integers and the operation addition "+", denoted (Z,+), the operation + combines any two integers to form a third integer, addition is associative, zero is the additive identity, every integer n has an additive inverse, −n, and the addition operation is commutative since m + n = n + m for any two integers m and n.

- Every cyclic group G is abelian, because if x, y are in G, then xy = aman = am + n = an + m = anam = yx. Thus the integers, Z, form an abelian group under addition, as do the integers modulo n, Z/nZ.

- Every ring is an abelian group with respect to its addition operation. In a commutative ring the invertible elements, or units, form an abelian multiplicative group. In particular, the real numbers are an abelian group under addition, and the nonzero real numbers are an abelian group under multiplication.

- Every subgroup of an abelian group is normal, so each subgroup gives rise to a quotient group. Subgroups, quotients, and direct sums of abelian groups are again abelian.

In general, matrices, even invertible matrices, do not form an abelian group under multiplication because matrix multiplication is generally not commutative. However, some groups of matrices are abelian groups under matrix multiplication - one example is the group of 2x2 rotation matrices.

Historical remarks

Abelian groups were named for Norwegian mathematician Niels Henrik Abel by Camille Jordan because Abel found that the commutativity of the group of an equation implies its roots are solvable by radicals. See Section 6.5 of Cox (2004) for more information on the historical background.

Properties

If n is a natural number and x is an element of an abelian group G written additively, then nx can be defined as x + x + ... + x (n summands) and (−n)x = −(nx). In this way, G becomes a module over the ring Z of integers. In fact, the modules over Z can be identified with the abelian groups.

Theorems about abelian groups (i.e. modules over the principal ideal domain Z) can often be generalized to theorems about modules over an arbitrary principal ideal domain. A typical example is the classification of finitely generated abelian groups which is a specialization of the structure theorem for finitely generated modules over a principal ideal domain. In the case of finitely generated abelian groups, this theorem guarantees that an abelian group splits as a direct sum of a torsion group and a free abelian group. The former may be written as a direct sum of finitely many groups of the form Z/pkZ for p prime, and the latter is a direct sum of finitely many copies of Z.

If f, g : G → H are two group homomorphisms between abelian groups, then their sum f + g, defined by (f + g)(x) = f(x) + g(x), is again a homomorphism. (This is not true if H is a non-abelian group.) The set Hom(G, H) of all group homomorphisms from G to H thus turns into an abelian group in its own right.

Somewhat akin to the dimension of vector spaces, every abelian group has a rank. It is defined as the cardinality of the largest set of linearly independent elements of the group. The integers and the rational numbers have rank one, as well as every subgroup of the rationals.

Finite abelian groups

Cyclic groups of integers modulo n, Z/nZ, were among the first examples of groups. It turns out that an arbitrary finite abelian group is isomorphic to a direct sum of finite cyclic groups of prime power order, and these orders are uniquely determined, forming a complete system of invariants. The automorphism group of a finite abelian group can be described directly in terms of these invariants. The theory had been first developed in the 1879 paper of Georg Frobenius and Ludwig Stickelberger and later was both simplified and generalized to finitely generated modules over a principal ideal domain, forming an important chapter of linear algebra.

Classification

The fundamental theorem of finite abelian groups states that every finite abelian group G can be expressed as the direct sum of cyclic subgroups of prime-power order. This is a special case of the fundamental theorem of finitely generated abelian groups when G has zero rank.

The cyclic group  of order mn is isomorphic to the direct sum of

of order mn is isomorphic to the direct sum of  and

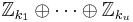

and  if and only if m and n are coprime. It follows that any finite abelian group G is isomorphic to a direct sum of the form

if and only if m and n are coprime. It follows that any finite abelian group G is isomorphic to a direct sum of the form

in either of the following canonical ways:

- the numbers k1,...,ku are powers of primes

- k1 divides k2, which divides k3, and so on up to ku.

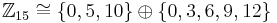

For example,  can be expressed as the direct sum of two cyclic subgroups of order 3 and 5:

can be expressed as the direct sum of two cyclic subgroups of order 3 and 5:  . The same can be said for any abelian group of order 15, leading to the remarkable conclusion that all abelian groups of order 15 are isomorphic.

. The same can be said for any abelian group of order 15, leading to the remarkable conclusion that all abelian groups of order 15 are isomorphic.

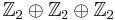

For another example, every abelian group of order 8 is isomorphic to either  (the integers 0 to 7 under addition modulo 8),

(the integers 0 to 7 under addition modulo 8),  (the odd integers 1 to 15 under multiplication modulo 16), or

(the odd integers 1 to 15 under multiplication modulo 16), or  .

.

See also list of small groups for finite abelian groups of order 16 or less.

Automorphisms

One can apply the fundamental theorem to count (and sometimes determine) the automorphisms of a given finite abelian group G. To do this, one uses the fact (which will not be proved here) that if G splits as a direct sum H  K of subgroups of coprime order, then Aut(H

K of subgroups of coprime order, then Aut(H  K)

K)  Aut(H)

Aut(H)  Aut(K).

Aut(K).

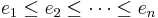

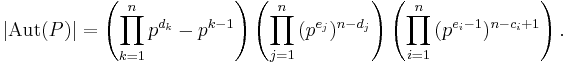

Given this, the fundamental theorem shows that to compute the automorphism group of G it suffices to compute the automorphism groups of the Sylow p-subgroups separately (that is, all direct sums of cyclic subgroups, each with order a power of p). Fix a prime p and suppose the exponents ei of the cyclic factors of the Sylow p-subgroup are arranged in increasing order:

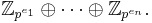

for some n > 0. One needs to find the automorphisms of

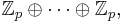

One special case is when n = 1, so that there is only one cyclic prime-power factor in the Sylow p-subgroup P. In this case the theory of automorphisms of a finite cyclic group can be used. Another special case is when n is arbitrary but ei = 1 for 1 ≤ i ≤ n. Here, one is considering P to be of the form

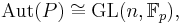

so elements of this subgroup can be viewed as comprising a vector space of dimension n over the finite field of p elements  . The automorphisms of this subgroup are therefore given by the invertible linear transformations, so

. The automorphisms of this subgroup are therefore given by the invertible linear transformations, so

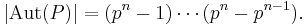

where GL is the appropriate general linear group. This is easily shown to have order

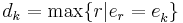

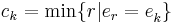

In the most general case, where the ei and n are arbitrary, the automorphism group is more difficult to determine. It is known, however, that if one defines

and

then one has in particular dk ≥ k, ck ≤ k, and

One can check that this yields the orders in the previous examples as special cases (see [Hillar,Rhea]).

Infinite abelian groups

Тhe simplest infinite abelian group is the infinite cyclic group Z. Any finitely generated abelian group A is isomorphic to the direct sum of r copies of Z and a finite abelian group, which in turn is decomposable into a direct sum of finitely many cyclic groups of primary orders. Even though the decomposition is not unique, the number r, called the rank of A, and the prime powers giving the orders of finite cyclic summands are uniquely determined.

By contrast, classification of general infinitely generated abelian groups is far from complete. Divisible groups, i.e. abelian groups A in which the equation nx = a admits a solution x ∈ A for any natural number n and element a of A, constitute one important class of infinite abelian groups that can be completely characterized. Every divisible group is isomorphic to a direct sum, with summands isomorphic to Q and Prüfer groups Qp/Zp for various prime numbers p, and the cardinality of the set of summands of each type is uniquely determined.[2] Moreover, if a divisible group A is a subgroup of an abelian group G then A admits a direct complement: a subgroup C of G such that G = A ⊕ C. Thus divisible groups are injective modules in the category of abelian groups, and conversely, every injective abelian group is divisible (Baer's criterion). An abelian group without non-zero divisible subgroups is called reduced.

Two important special classes of infinite abelian groups with diametrically opposite properties are torsion groups and torsion-free groups, examplified by the groups Q/Z (periodic) and Q (torsion-free).

Torsion groups

An abelian group is called periodic or torsion if every element has finite order. A direct sum of finite cyclic groups is periodic. Although the converse statement is not true in general, some special cases are known. The first and second Prüfer theorems state that if A is a periodic group and either it has bounded exponent, i.e. nA = 0 for some natural number n, or if A is countable and the p-heights of the elements of A are finite for each p, then A is isomorphic to a direct sum of finite cyclic groups.[3] The cardinality of the set of direct summands isomorphic to Z/pmZ in such a decomposition is an invariant of A. These theorems were later subsumed in the Kulikov criterion. In a different direction, Helmut Ulm found an extension of the second Prüfer theorem to countable abelian p-groups with elements of infinite height: those groups are completely classified by means of their Ulm invariants.

Torsion-free and mixed groups

An abelian group is called torsion-free if every non-zero element has infinite order. Several classes of torsion-free abelian groups have been extensively studied:

- Free abelian groups, i.e. arbitrary direct sums of Z

- Cotorsion and algebraically compact torsion-free groups such as the p-adic integers

- Slender groups

An abelian group that is neither periodic nor torsion-free is called mixed. If A is an abelian group and T(A) is its torsion subgroup then the factor group A/T(A) is torsion-free. However, in general the torsion subgroup is not a direct summand of A, so the torsion-free factor cannot be realized as a subgroup of A and A is not isomorphic to T(A) ⊕ A/T(A). Thus the theory of mixed groups involves more than simply combining the results about periodic and torsion-free groups.

Invariants and classification

One of the most basic invariants of an infinite abelian group A is its rank: the cardinality of the maximal linearly independent subset of A. Abelian groups of rank 0 are precisely the periodic groups, while torsion-free abelian groups of rank 1 are necessarily subgroups of Q and can be completely described. More generally, a torsion-free abelian group of finite rank r is a subgroup of Qr. On the other hand, the group of p-adic integers Zp is a torsion-free abelian group of infinite Z-rank and the groups Zpn with different n are non-isomorphic, so this invariant does not even fully capture properties of some familiar groups.

The classification theorems for finitely generated, divisible, countable periodic, and rank 1 torsion-free abelian groups explained above were all obtained before 1950 and form a foundation of the classification of more general infinite abelian groups. Important technical tools used in classification of infinite abelian groups are pure and basic subgroups. Introduction of various invariants of torsion-free abelian groups has been one avenue of further progress. See the books by Irving Kaplansky, László Fuchs, Phillip Griffiths, and David Arnold, as well as the proceedings of the conferences on Abelian Group Theory published in Lecture Notes in Mathematics for more recent results.

Additive groups of rings

The additive group of a ring is an abelian group, but not all abelian groups are additive groups of rings (with nontrivial multiplication). Some important topics in this area of study are:

- Tensor product

- Corner's results on countable torsion-free groups

- Shelah's work to remove cardinality restrictions

Relation to other mathematical topics

Many large abelian groups possess a natural topology, which turns them into topological groups.

The collection of all abelian groups, together with the homomorphisms between them, forms the category Ab, the prototype of an abelian category.

Nearly all well-known algebraic structures other than Boolean algebras, are undecidable. Hence it is surprising that Tarski's student Szmielew (1955) proved that the first order theory of abelian groups, unlike its nonabelian counterpart, is decidable. This decidability, plus the fundamental theorem of finite abelian groups described above, highlight some of the successes in abelian group theory, but there are still many areas of current research:

- Amongst torsion-free abelian groups of finite rank, only the finitely generated case and the rank 1 case are well understood;

- There are many unsolved problems in the theory of infinite-rank torsion-free abelian groups;

- While countable torsion abelian groups are well understood through simple presentations and Ulm invariants, the case of countable mixed groups is much less mature.

- Many mild extensions of the first order theory of abelian groups are known to be undecidable.

- Finite abelian groups remain a topic of research in computational group theory.

Moreover, abelian groups of infinite order lead, quite surprisingly, to deep questions about the set theory commonly assumed to underlie all of mathematics. Take the Whitehead problem: are all Whitehead groups of infinite order also free abelian groups? In the 1970s, Saharon Shelah proved that the Whitehead problem is:

- Undecidable in ZFC, the conventional axiomatic set theory from which nearly all of present day mathematics can be derived. The Whitehead problem is also the first question in ordinary mathematics proved undecidable in ZFC;

- Undecidable even if ZFC is augmented by taking the generalized continuum hypothesis as an axiom;

- Decidable if ZFC is augmented with the axiom of constructibility (see statements true in L).

A note on the typography

Among mathematical adjectives derived from the proper name of a mathematician, the word "abelian" is rare in that it is often spelled with a lowercase a, rather than an uppercase A, indicating how ubiquitous the concept is in modern mathematics.[4]

See also

- Abelianization

- Class field theory

- Commutator subgroup

- Elementary abelian group

- Pontryagin duality

- Pure injective module

- Pure projective module

Notes

- ^ Jacobson (2009), p. 41

- ^ For example, Q/Z ≅ ∑p Qp/Zp.

- ^ Countability assumption in the second Prüfer theorem cannot be removed: the torsion subgroup of the direct product of the cyclic groups Z/pmZ for all natural m is not a direct sum of cyclic groups.

- ^ Abel Prize Awarded: The Mathematicians' Nobel

References

- Cox, David (2004). Galois Theory. Wiley-Interscience. MR2119052.

- Fuchs, László (1970). Infinite Abelian Groups, Vol. I. Pure and Applied Mathematics. 36-I. Academic Press. MR0255673.

- Fuchs, László (1973). Infinite Abelian Groups, Vol. II. Pure and Applied Mathematics. 36-II. Academic Press. MR0349869.

- Griffith, Phillip A. (1970). Infinite Abelian group theory. Chicago Lectures in Mathematics. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-30870-7.

- Herstein, I. N. (1975). Topics in Algebra (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-02371-X.

- Hillar, Christopher; Rhea, Darren (2007). "Automorphisms of finite abelian groups". American Mathematical Monthly 114 (10): 917–923. arXiv:math/0605185.

- Jacobson, Nathan (2009). Basic Algebra I (2nd ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-47189-1.

- Szmielew, Wanda (1955). "Elementary properties of abelian groups". Fundamenta Mathematicae 41: 203–271.